UNMASTERED

Tavares Strachan | Jeffery Meris | Stan Burnside

Pablo Picasso | Joan Miró | Antoni Tapies

December 4th 2020 - March 4th 2021

Unmastered: the recording music term that describes a raw digital recording that has not beencleaned up for audio consumption.

Reggae, a style of music steeped in African tradi- tion, is at the heart of Western contemporary music. Derived from colloquial Caribbean expression “rege rege,” meaning rags or raggy clothes, this was also a commonplace way to describe a poor black person from the Caribbean. A massive part of the Afro-Caribbean experience is marked by well-doc- umented, substandard living conditions created by the colonial project. The invention of reggae waslargely defined by this very lack of access to base levelnecessities, such as quality food, running water and access to education. These disadvantages resulted in the socio-economic trauma experienced by black people throughout the Caribbean. Like the history of dub and hip-hop, the production of reggae music derived from a lack of access to traditional instru- ments and recording equipment. The Caribbean boy used a boom box or used records to make music outof necessity, reflecting a particular kind of masterywithin this struggle. Born from struggle and inequity, this art form is the foundation of almost all of world music and by extension world culture.

Unmastered: a reframing of the idea of a “master” which inherently has been framed by a Eurocentric lens.

To disarm this term, we must understand how itfunctions, and who benefits from it. This means we must interrogate the works of masters such as Picasso and Miró next to Afro-futurists such as Stan Burnside. We must trade in our Eurocentric toolbox for processing the world for one that places value on creative practice based of both cause andeffect. Pablo Picasso’s Negro or African period isessentially a reinterpretation of African masks. This sampling of material from the African continent is singularly responsible for the development of a European avant-garde, forming Modernism. I am not interrogating sampling as a means of inspiration or making the claim that Picasso is less important because he and many of his peers sampled Africa. In fact, I am postulating that artists such as Picasso and Miró are part of a universal creative pool that all artists share, regardless of race, color, or creed. It is important to understand that every tree has a root, and for a large portion of culture that root is deeply African. When asked to curate this exhibi-tion, I reflected on my own artistic practice. I spentthe past eight years researching hidden histories and through this work I became fascinated with making the invisible aspects of history visible. This research has led me to the place where I am concerned withhow things are more similar than how they are differ- ent. Curating this exhibition was also wonderful opportunity for me to talk about the long history of Afro-surrealism that lives in the Caribbean. In 2009, historian Scot Miller famously wrote in the Afro-Surreal Manifesto, “Afro-Surrealism sees that all others who create from their actual, lived experi- ences are surrealist.” The diasporic struggle is both real to the person in the struggle, and mostly unfathomable to an outsider. Stan Burnsideand Jeffery Meris are examples of artists makingfrom their lived experience. Burnside has a unique way of telling the story of living as a Bahamian, as a form of magic that evolved from struggle.

A disciplined colorist and an expert historian, Burnside helps us better understand the expression “drawing blood from a stone.”

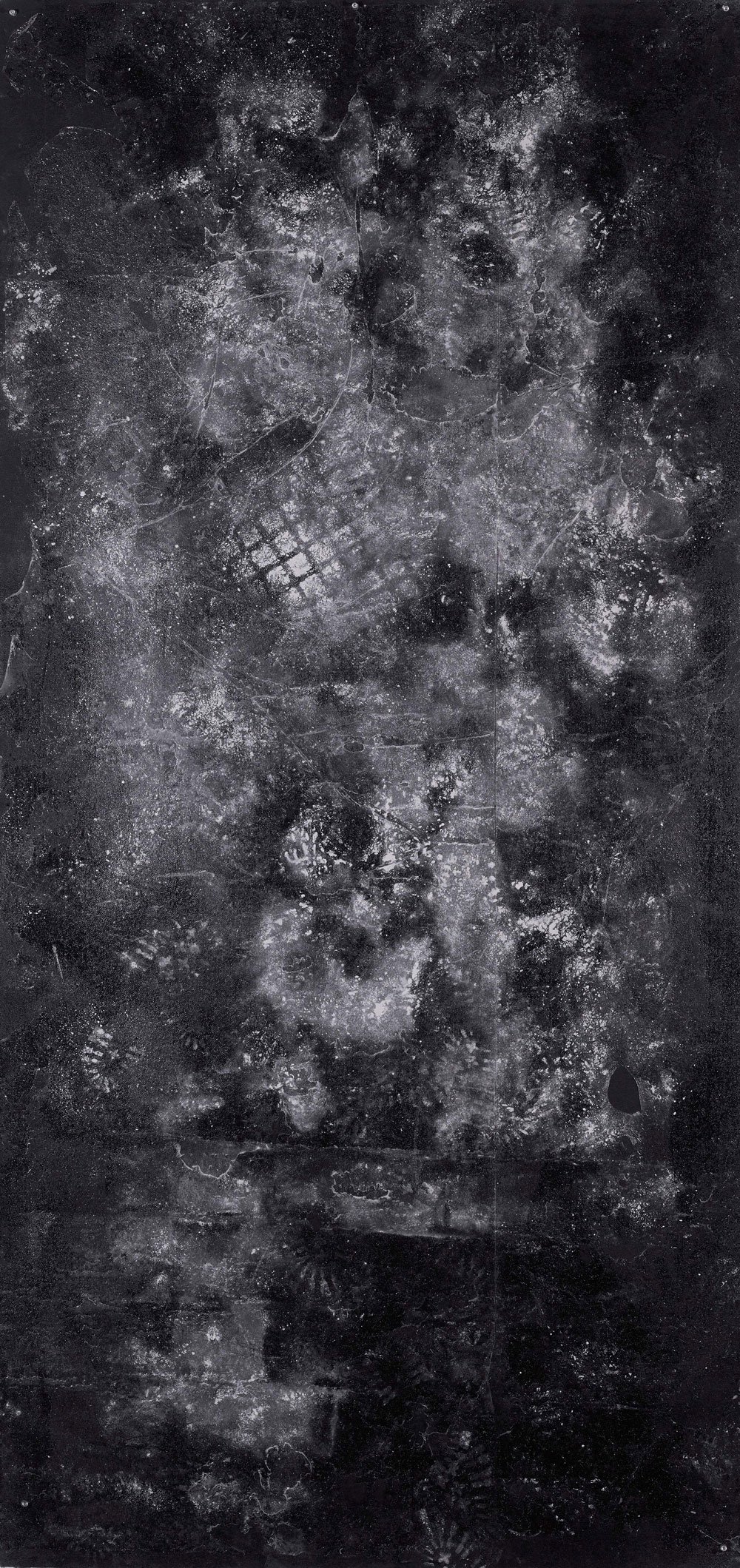

Meris, on the other hand, examines his experienceas an immigrant, specifically the toll that social andphysiological stresses take on the body. For his works in the exhibition, Meris renders raw material from his performances and kinetic sculptures into ways of measuring and recording activity. These worksare made by placing paper on the floor, picking upwhat was left, and making these drawings a form of material surveillance.

If the question is what do all of these artists have in common, the answer is everything. All of these works are connected, and it is up to us to re-organize those structures that value one work over another based on arbitrary dividing lines. We know based on our collective experience that we must reject the idea that something is better purely based on the fact that its producer is European. Picasso and the Modernists taught us that a long time ago. We also know that by principle of our universe, everything is connected. The relationships between artists transcend time and space. In this sense, Pablo Picasso is surely having a conversation with Stan Burnside.

- Tavares Strachan

Tavares Strachan | Distant Relatives (Sister Nancy), 2020 Fang Mask (Gabon), pigment, natural fibers, plaster, brass, acrylic 19 in L x 32 W x 62 in H

Tavares Strachan | Distant Relatives (W.E.B. Dubois), 2020 Pende Mask (DR Congo), pigment, natural fibers, plaster, brass, acrylic 24 L x 20 in W x 67in H

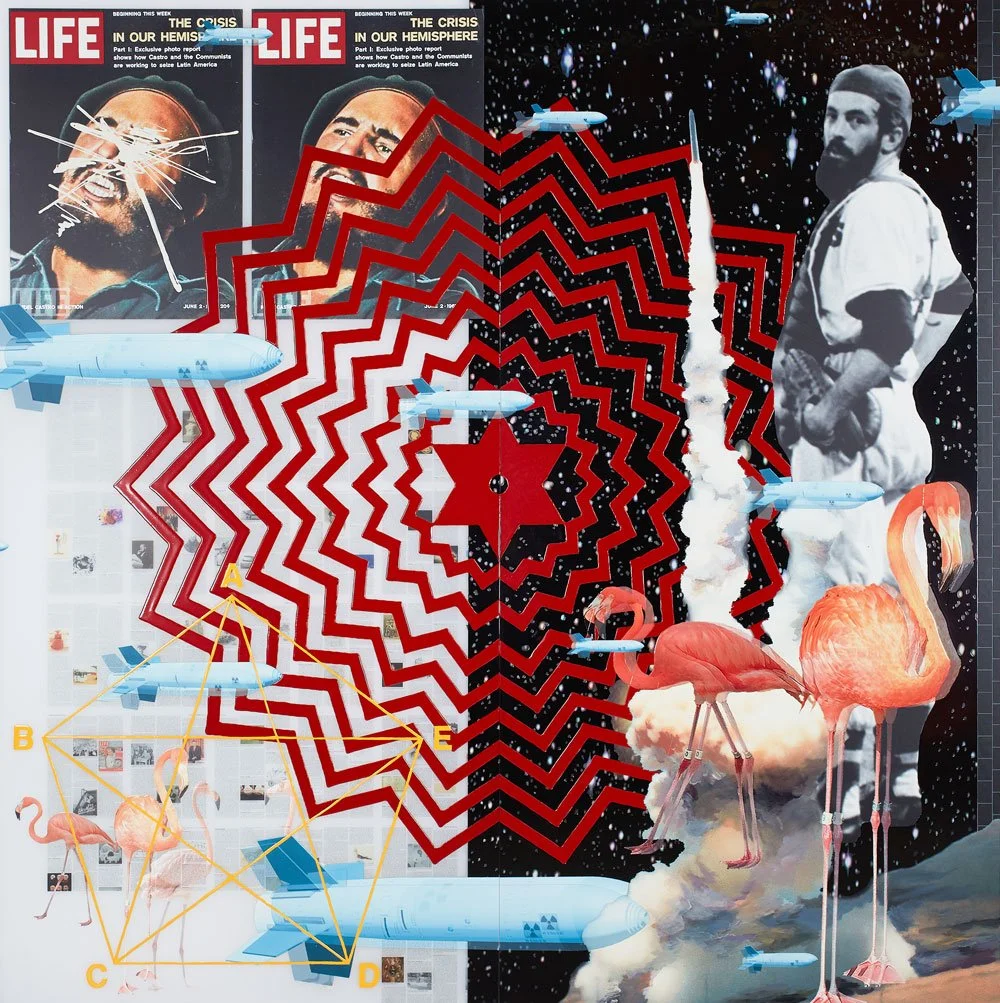

Tavares Strachan | In Our Hemisphere, 2020 Oil, enamel, and pigment on acrylic 84 x 42 x 2 in each

Jeffrey Meris | I, Used To Be (X), 2020 Plaster Particles on Roofing Paper, Double Sided Adhesive Tape, plexi, sintra 79 in x 36 in

Jeffrey Meris | I, Used To Be (XI), 2020 Plaster Particles on Roofing Paper, Double Sided Adhesive Tape, plexi, sintra 79 in x 36 in

Jeffrey Meris | I, Used To Be (XII), 2020 Plaster Particles on Roofing Paper, Double Sided Adhesive Tape, plexi, sintra 79 in x 36 in

Stan Burnside | Return of the King, 2019 60 x 80.5 in (diptych) Acrylic on Canvas

Stan Burnside | Celestial Navigator: Hometown Philosopher, 2019 Acrylic on canvas 60 x 40 in

Stan Burnside | Visionary Princess with Matissian Hands: You Gotta See What it is Yer Lookin’ At, 2019 Acrylic on Canvas 60 x 40 in

Tapies | Dau al Set. Pequena Acuarela II, 1949 Watercolour and ink on paper 34.4 X 24.7 cm

Tapies | Pequena AcuarelaI. Dau al Set, 1949 Watercolour and ink on paper 34.4 X 24.7 cm

Pablo Picasso | Home a la Moustache, 1970 Oil on wood 129 x 66.5 cm

Pablo Picasso | Femme en Buste/ Buste de femme couchee, 1939 Conte crayon on vellum 48.3 x 63.3 cm

Joan Miro | Figure devant la lune, 1942 Gouache, India ink and pastel on paper 64 x 48 cm/ 25.25 x 18.88 in

Joan Miro | Oleo sobre carton, 1960 Oil on cardboard 105 x 75 cm