A PLACE OUTSIDE THE LAW

Stefan Brüggemann &

Gardar Eide Einarsson

November 20th 2021 - February 27th 2022

In 1718 Woodes Rogers, once a successful privateer, was appointed an initial term as Royal Governor of the failed British colony of The Bahamas, tasked with a sole mandate to sanitize Nassau, the global headquarters, of piracy. It was during his administration The Bahamas' first motto "Expulsis, Piratis, Restituta Commercia" (Pirates Expelled, Commerce Restored) was coined. Before him stood menacing outlaws, “supergangs” committing acts of skullduggery, particularly during this period referred to as the “Golden Age of Piracy”. They controlled vast areas in and around the Caribbean region reaching as far north as Bermuda and the Carolinas, occupying many British outposts and amassing wealth, which was used to gain the loyalty of merchants, plantation owners and governors. For some these were persona non grata figures such as “Blackbeard”, “Black Sam” and “Calico Jack'' who are nothing short of folk legends for others. They had the audacity to disrupt global trade routes along with the plantation supply chains of the established ruling New World empires and in so doing, eked out an egalitarian existence irrespective of race, gender or creed, accompanied by a system of law codes beyond the confines of the colonial metropole. Welcome to the “Pirates Republic”.

Undoubtedly, the “Golden Age” has captured the collective imagination for centuries, churning out endless hackneyed cultural material, either imagined or real, of pirate archetypes. But why such romanticisation of and enduring appetite for these artifacts? In part, the work in this exhibition by Bruggeman and Einarsson is a provocation into this phenomenon worth positing. On one hand it offers a glimpse into the ongoing iconography and the process of simulacra--images reproduced, altered, distributed and excessively consumed to become a derivative of the original, becoming something new with its own identity. Jean Baudrillard refers to this as the “hyper-reality”--a hyper-connected world of internet, television and other media. On the other hand, and perhaps more importantly, the seafaring, nomadic pirate who exists outside the limits of civilized “ordered” society becomes encoded into the dichotomy of the nature-wilderness condition. Simply, if beauty is linked to pleasure and nature, wild or wilderness is associated with danger, terror and self-preservation and pervaded by what 18th century Romantic poets defined as the “sublime”--a feeling of being exposed to the natural elements along with the presence of God. But even more, a life filled with risks and uncertainty while being preoccupied with self-preservation in the here and now. According to Edmund Burke, 18th century philosopher, in his A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), as much as the pirate is held to be the quintessential romantic outlaw, the ocean is seen as the ultimate wilderness space and with it the sublime.

In 1728, Woodes Rogers was reappointed as Royal Governor for a second term by King George II and died a few years later in Nassau in 1732. It is debatable whether or not he was able to achieve his mission to truly rid this colony of piracy given its pervasiveness.

We sympathize with the plight of pirates because they are transposed in us and over time their mythology is part of our psyche. Perhaps we should consider a new motto, “Restituta Piratis, Expulsis Commercia” (Pirates Restored, Commerce Expelled).“Arrr!”

-Michael Edwards

Gardar Eide Einarsson Mutiny! Pirate Tactics, 2021 Acrylic, graphite and gesso on canvas 64" x 64"

Gardar Eide Einarsson A Place Outside the Law, 2021 Acrylic, graphite and gesso on canvas 71" x 86.75"

Gardar Eide Einarsson Enough of Poverty and Idleness! I Shall Return to the Work I Love – Beheading. 2021, Acrylic, graphite and gesso on canvas, 63" x 63"

Stefan Brüggemann Free Trade, in Gold We Trust, 2021 Spray, oil and gold leaf on canvas 78.75" x 73"

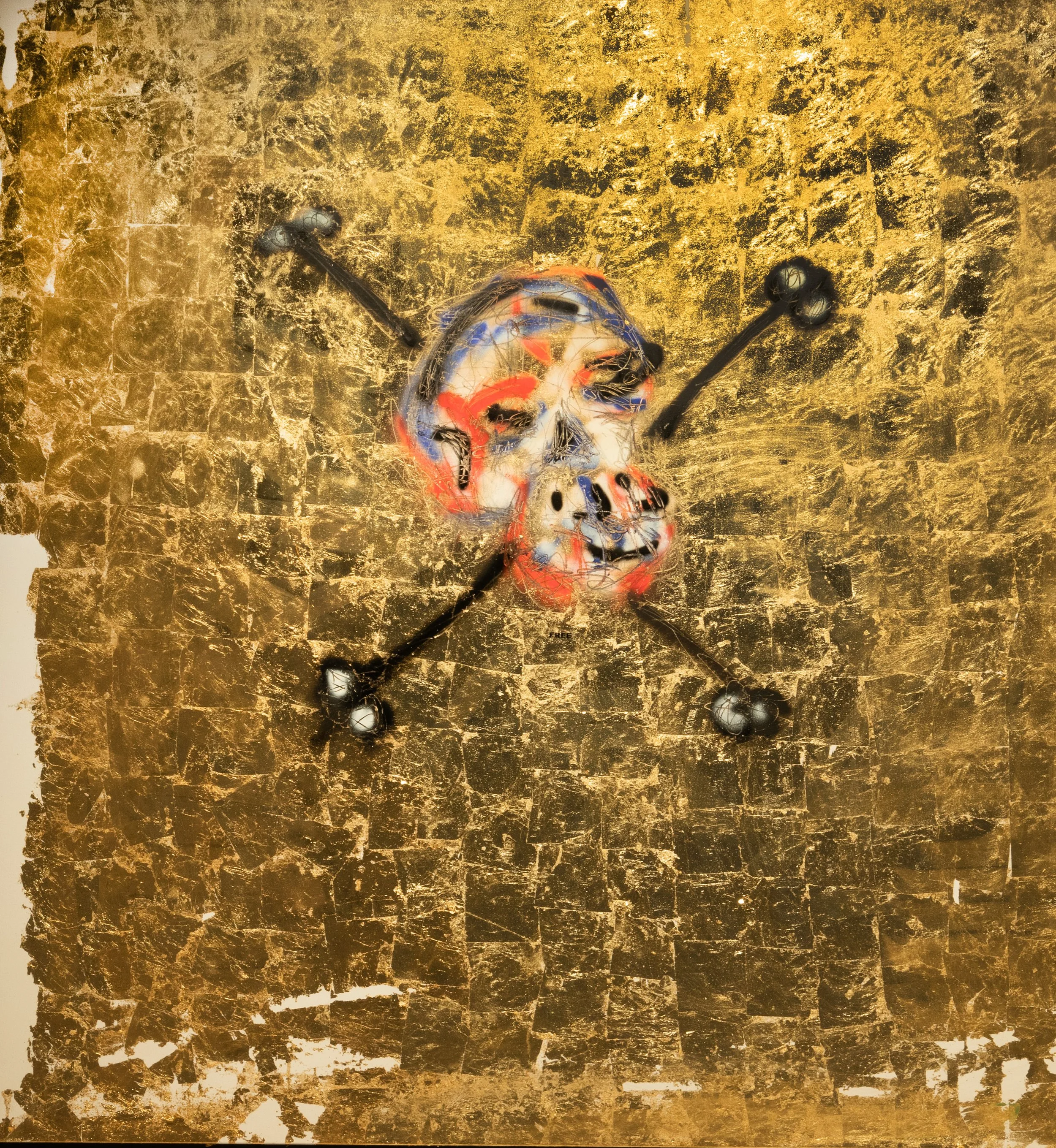

Stefan Brüggemann Pirate, 2021 Spray, oil and gold leaf on canvas 59" x 59"

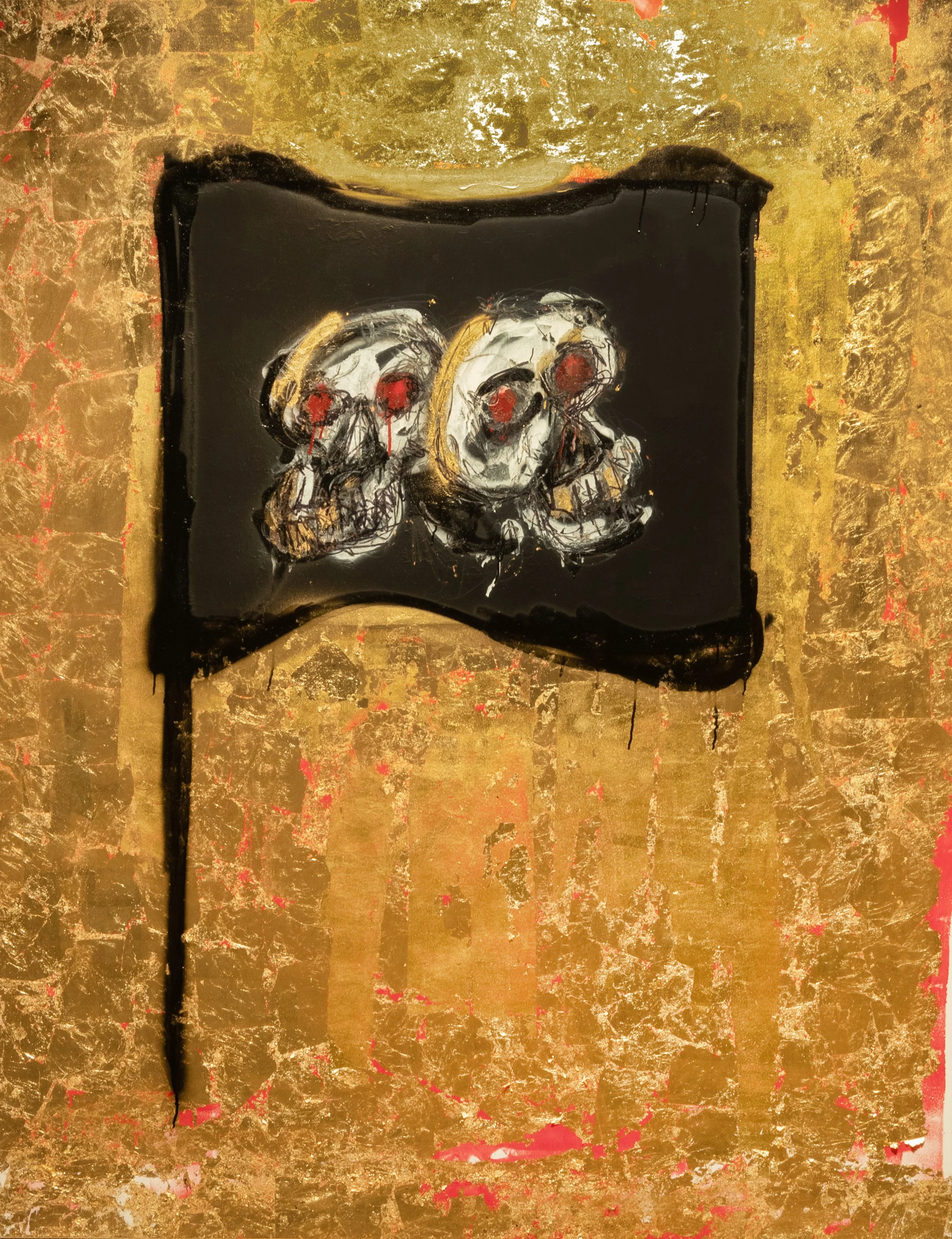

Stefan Brüggemann Black Flag, 2021 Spray, oil and gold leaf on canvas 78.75 x 63"

Stefan Brüggemann Pirates of the Caribbean, 2021 Spray, oil and gold leaf on canvas 78.75" x 61"