QUARANTINO’S

LULLABY

Stan Burnside

December 9th 2022 - March 1st 2023

“The way you get to know yourself is by the expressions on other people's faces, because that's the only thing that you can see, unless you carry a mirror about.”

- Gil Scott-Heron

In his new body of work, the exhibition titled “QUARANTINO’S LULLABY,” the artist binds the physical with the metaphysical, grounding that which is weightless. In a way that only Stan Burnside can express, this new body of work holds a certain record of our time in “lockdown.” From a palette of purple, he extends this idea as a metaphor that speaks of a timeless, interconnected struggle of the people who inhabit this island. This isolation only leaves humanity when we accept a universal language of togetherness. It's a kind of isolation that lasts beyond a pandemic, if we allow it. Burnside pulls this exact feeling of pandemic-era isolation from the ground, like a seed sprouting into the air.

As you stare at each figure in these paintings, let them reflect their deep inner affection that goes from mother to child, brother to sister. With paint, the artist empowers his subjects with human dignity. Their stories manifest the rainbow of human experience and conveys an enduring truth: To everything there is a cycle. To light, there is the dark, and with the morning, night follows. Born through isolation, these characters are painted into a world of power and gratification.

In the words of the artist, “The pandemic brought me face to face with time, and how valuable time is. In one sense, it allowed me the absolute freedom to work in my studio space because there was less pressure from the outside world, even though it was a rough, rough period. But it also made me cognizant of how limited time is and how valuable time is, and how I have to take advantage of what time I have left.”

With time, a painter reveals the souls of our people with eloquence. In these paintings we can find the joy to counter our tragedy. We counter the loss of time, and we discover timelessness.

- Tavares Strachan

Tavares Strachan in conversation with Stan Burnside

Introduction:

Tavares: Tell me about Qurantino's lullaby.

Stan: Quarantino's lullaby is Madonna and child revisited. The fact that Jesus was born during a time just like this, it was bleak and people were struggling and suffering. In fact, he had to be born in a manger, and yet he was born. And Qurantino has to do with children who are born during these rough, rough times. You can only imagine some of the struggles of mothers to just keep their children safe during this time. So it was that thought. And in discussion with my curator, a brilliant guy, by the way, he thought the Qurantino's lullaby really described the whole body of work. But that was the foundation of the body of work.

1 - Painting

TS: Out of all of the tools you could use to tell your story, why paint?

SB: Because it's a language that I feel most comfortable with. It's a language that I have been using for 50 years. As a painter, I'm very selfish. I go inside of myself. And sometimes what I do has nothing to do with who's going to view the painting. It almost has to do with my communion with my own demons and my own understanding of the world. So that's why I paint.

TS: Talk to me about how intimate it is for you to paint the subject that you paint, knowing that people that are just close to you, like they're actually physically and spiritually and emotionally close to you.

SB: Well, actually that part is kind of amusing because when I paint them, they no longer have a relationship with me. They become just tools and props. They become actors, they become characters in this story that I'm telling. So it has nothing to do with them and my love of them and all of that. Like what I see when I look at your face, it has less to do with Tavares than what your face could represent.

TS: So the me inside of me and then the whole other character and all these other characters that are living in your head come out.

2 - Beauty

TS: When I look at the work, I find it to be mesmerizing. The aesthetics of it is like a Venus flytrap in a way, they woo you in with beauty. I know we're talking about all the history stuff in the 60’s stuff, but when you make food, you want it to taste good. And when you play music, you want it to sound good. So talk to me about beauty.

SB: It's interesting that you use the word mesmerized, because not to blow smoke, but I feel the same way about your work. But beauty for me has to do less with seeing than with feeling. If I can create an image that causes people to go beyond what they see, to feel something, then I think that is what I'm trying to communicate even more than the actual mechanics of the painting. I guess that's the poet in me, the beauty.

3 - Figuration

TS: You've seen a lot of trends in your time, and you've watched figuration come in and out of focus artistic production. What do you say to the abstractionist who's just like, “figuration is only skin deep?” What's your response to the abstractionist who says that?

SB: Well, I'm funny when it comes to painting. I don't see a separation between what a figurative painter does and what a good abstract painter does. I can feel the same feeling from colors and composition and line that I can from the expression on the face of an image in a painting. In fact, when I was in gradschool, sometimes I got more from the best figurative painters than from the abstract painters because they sort of went beyond just the literal representation of the figure, but both roads lead to great paintings.

4 - Color

TS: Say more about some of the decisions you made about the colors, the color palette you're using in the paintings.

SB: I guess the color palette, to a great extent, it's heavy on purple and violet, and it probably has a little to do with my upbringing in the Anglican Church. During Lent, everything is covered in purple, and I always saw purple as a sort of mournful kind of color, and some people think of it as royal, representing nobility and all of that, and I guess it represents that. But the color palette that I chose for this body of work has to do with that sort of poetry that is heavy on the violets and the purples and the lilacs and the light ultramarine blues.

5 - Church

TS: What are your thoughts on religion? How do you thread the needle of your ancestry, which is a decidedly different set of rituals and practices surrounding recognizing the ancestor versus the kind of the European setup traditions that are decidedly different?

SB: Well, the beautiful thing about being an artist is that you can create your own story around that. You know, fact is, Christianity started in Africa. There is a challenge that has to do with how the story is told. And that's really the genius of Walt Disney, that he created his own stories, he created his own fantasy, his own kind of thing. And so when I did a painting, Simon's Torment, it had to do with me challenging the version in the Bible of Simon of Cyrene’s contribution. The version in the Bible said that the guards forced him to take up the cross. But my version is that he went out there to help Jesus, and they were probably beating him to stop from helping Jesus. And we know from the way history is told, many stories get changed in order to deny credit to certain people. For example, they have these remarkable sculptures in Africa where the noses and lips were defaced so that the African features would disappear. So I'm just saying that we can create our own stories that we need. We need those stories for our people.

6 - Expectation

TS: You spend most of your life on the island. But when I see these paintings, I see a little bit of a rebellion. I see an acceptance of the reality of being on the island, but I also see, at the same time, rebellion of the island when I look at your palate. Talk to me about the idea of expectation.

SB: Well, I guess one of the reasons why I'm a painter, really is because I can do what I want to do, be my own boss and I have complete freedom. Junkanoo color, for example. I adore Junkanoo color, and I'm very proud of what we've achieved in creating a whole vocabulary of color usage in this country. And I think I'm fluent in Junkanoo color, but in my paintings, I don't restrict myself to Junkanoo color. And sometimes I have to depart from what is expected of an artist from our country to have the sense of color that is indicative of our culture.

7 - Past

TS: Is there any difference between what happened to you during the pandemic and what you're experiencing now? The pandemic was a deep moment of reflection for a lot of people. A lot of people had a lot of ideas and then time passed and here we are. And maybe they were able to make well on the promises, or maybe they didn't. What do you remember from then and how do you feel about it now?

SB: The Pandemic brought me face to face with time and how valuable time is. In one sense, it allowed me the absolute freedom to work in my studio space because there was less pressure from the outside world, even though it was a rough, rough period. I think for most artists, it created a natural sanctuary for all of us to produce work. But it also made me cognizant of how limited time is and how valuable time is and how I have to take advantage of what time I have left. The fact is, I lost a few people to Covid...and that was a shocker, because when I was your age, I don't think I realized I could die yet...But the pandemic and people dying and the rough circumstances, it made me appreciate more good people and communicating with good people and trying to be a good person to the people that I meet on the way.

8 - Future

TS: When you think about the future, what comes to mind for you? As someone who a lot of young folks look up to in the community, when you hear the word “future,” what emotions come up?

SB: I feel good about the future. Not to repeat myself. When I see some of the young artists like yourself doing things that create such hope and promise and possibilities for our people, that is something that gives me great satisfaction, man.

TS: How do you feel when I say that's an extension of you?

SB: Well, it certainly makes me feel fulfilled. I feel ownership of it because I feel like I know you, not just you and our relationship. But as I mentioned before, I was watched my uncle Sydney at the same point in his life, and it's the same kind of energy, the same kind of traveling, I guess, similar challenges, decisions having to be made, all of that. But I feel good about the future, man. But at the same time I recognize that there's some problems that we still have to come face to face with, and solve. And we will.

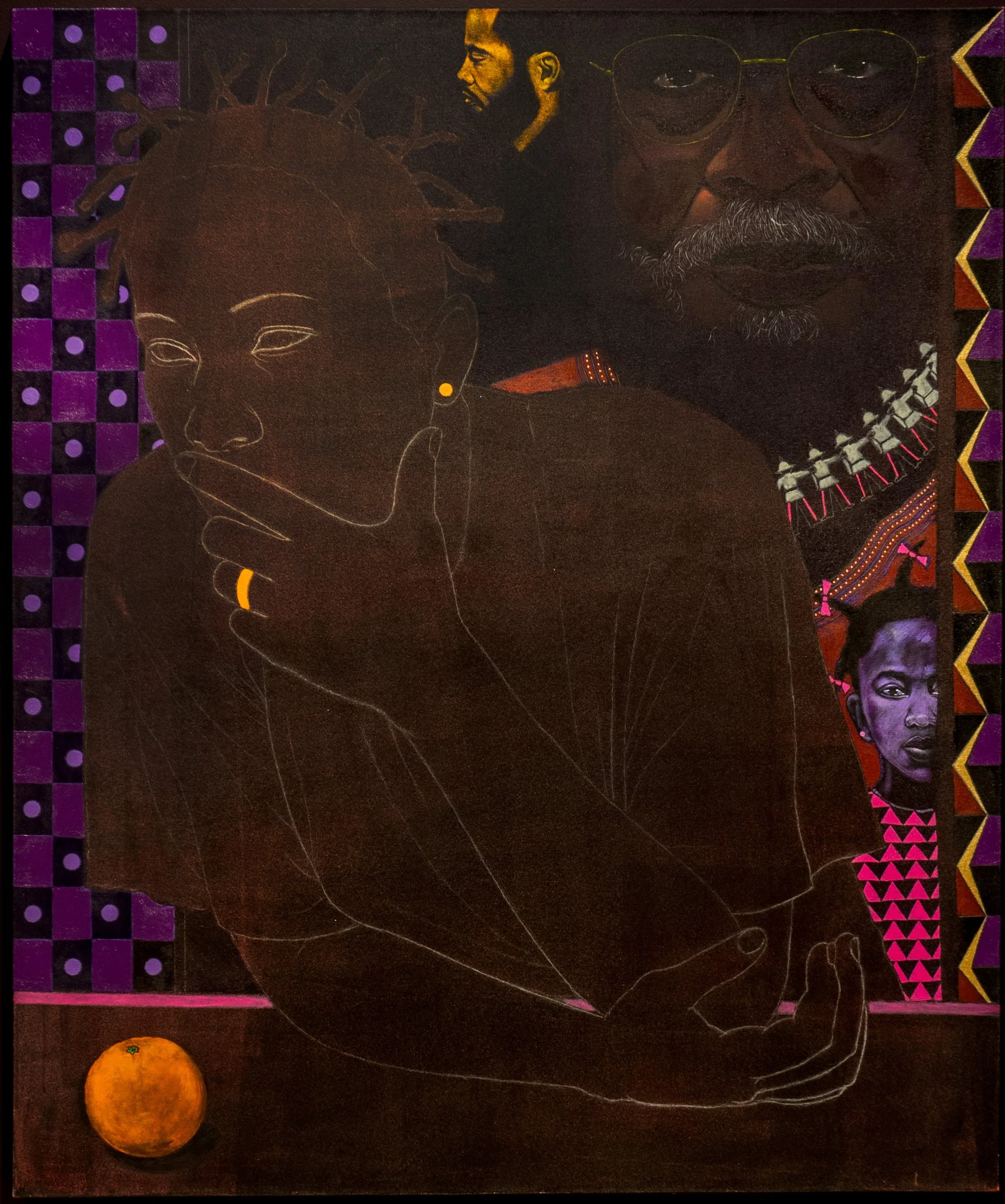

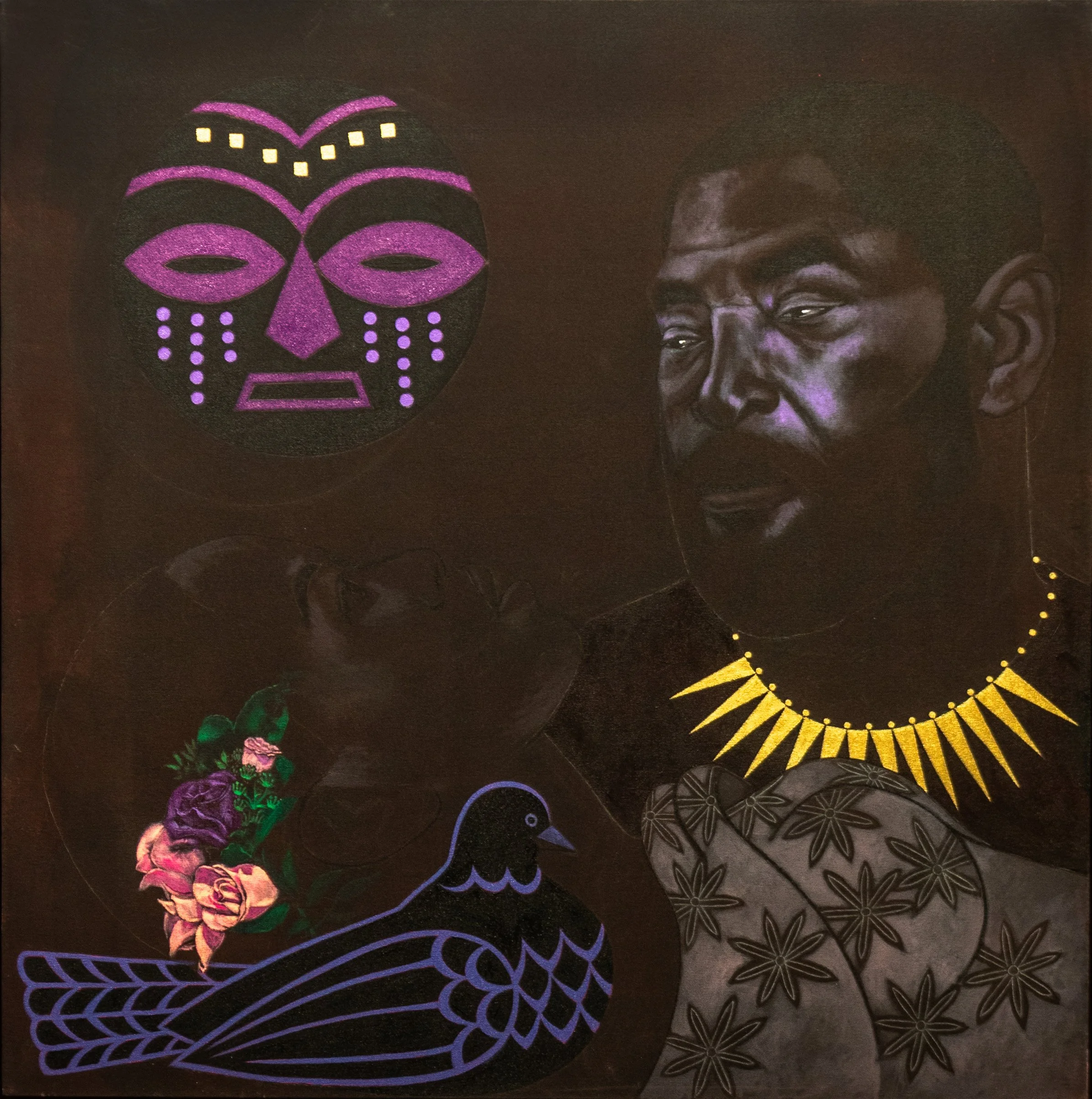

Quarantino's Lullaby, 2022 Acrylic on canvas with pastel marking 60" x 40"

A Prayer For Those Who Suffer In Silence: I See You!!!, 2022 Acrylic on canvas with pastel marking 74" x 144"

You Are Not Alone, 2022 Acrylic on canvas with pastel marking 47" x 47"

Ghost Stories, 2022 Acrylic on canvas with pastel marking 74.25" x 74"

The Wait of The World: Let Me Tinking, 2022 Acrylic on canvas with pastel marking 64.25" x 52

Tender Mercies, 2022 Acrylic on canvas with pastel marking 47" x 47"

Purple Reign, 2022 Acrylic on canvas with pastel marking 68" x 96"

Wonderland, 2022 Acrylic on canvas with pastel marking 47" x 47"