BLACKS AND THE BLUES

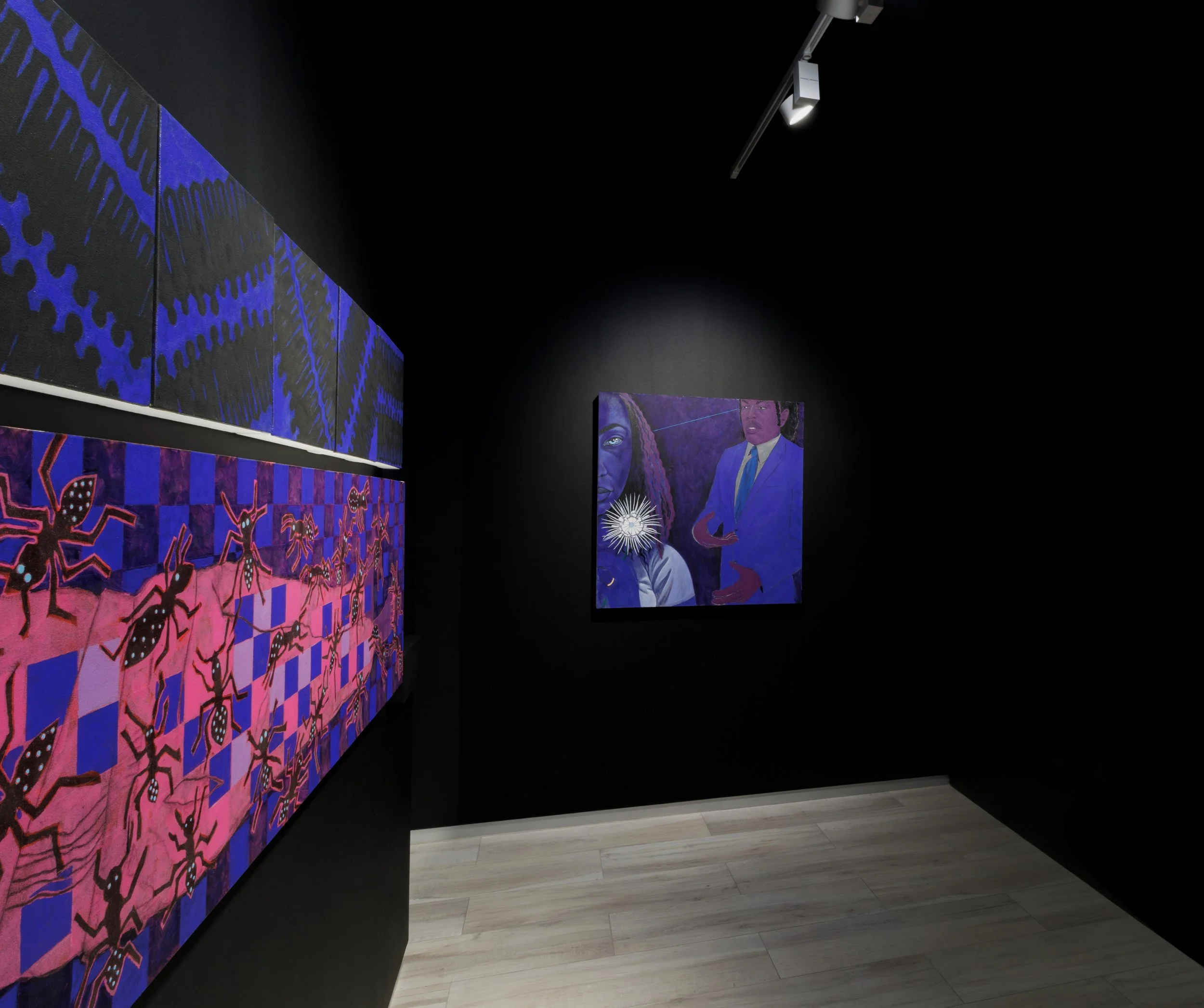

Stan Burnside

December 19th - February 15th 2025

Stan Burnside’s Lyrical “Blacks & the Blues”: Deep Chords of Sorrow and Marginality, Sweet Melodies of Triumph.

© Patricia Glinton-Meicholas 2024

With his Blacks and the Blues, artist Stan Burnside, a devoted son of The Bahamas takes an unvarnished look at Bahamian heritage and culture today. In equal measure, he posits issues of gender and race-based inequalities and inequities, all impacted by the two-faced issues and realities of modern life at home and universally. Evident in the messaging are deep contrasts—the heavenly and hellish, beauty and bigotry, hope and despair that leap across purposefully constructed race and gender divisions and barriers.

On the canvases of Blacks and the Blues (about twenty or so), we can discern Burnside’s deeply felt view on these persistent and daunting challenges. Clear also are his animating principles, deep thought and mystical command of line and color, all bound up in the artist’s unique brand of surrealism. These new works prove gripping and unforgettable on a multiplicity of levels. Readily perceived is unity of thought, beauty of form and style, sustained by wordplay in titles, poetic metaphors in paint and the canny juxtaposition of elements on the canvases. All told, these gripping mind teasers invite art and mystery lovers to engage a delightful and memorable voyage of discovery.

Themes

Thematically and stylistically, Blacks and the Blues is sister to Burnside’s 2022 collection Quarantino’s Lullabywhich was exhibited at Mestre Project at Albany, Nassau. Here now is Burnside’s newest exploration and revaluing of Bahamian culture and everyday realities. Here are blacks and “the blues” which, like the music genre, convey both the sorrow and survivalist traits of descendants of Africans who were enslaved in the Americas and the Caribbean for centuries. Also expressed are Stan’s deep concerns about developments occurring worldwide, which are once again impacting freedom.

Consider the ever-present threat of the denial of freedom in some form or other to blacks and others judged inferior in the courts of bigotry, whether manifested in random car stops and/or a greater than average rate of arrests and incarceration, either deserved or prejudicially imposed. Burnside clearly views the latter as a poisonous weed that has strangled the growth and development of untold numbers of black males, especially youths.

Similarly reflected across Blacks and the Blues is the artist’s deep concern for women who continue to be regarded as “the lesser man”, as in British poet Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Victorian estimation. Women continue to suffer age-old inequities in relationships, obligations and in the scant recognition of their personal and collective worth. Of all races, colors and ethnicities, women are an ever-vulnerable underclass engaged in a never-ending struggle for survival and dignity. Contributing factors and views tend to be deeply embedded, passed on and accepted without reflection. All too often, they feed anger, anguish, poverty, violence and societal turbulence endangering families and futures everywhere. With clever artistry, Stan Burnside causes us to look and reflect on these great ironies of democracy.

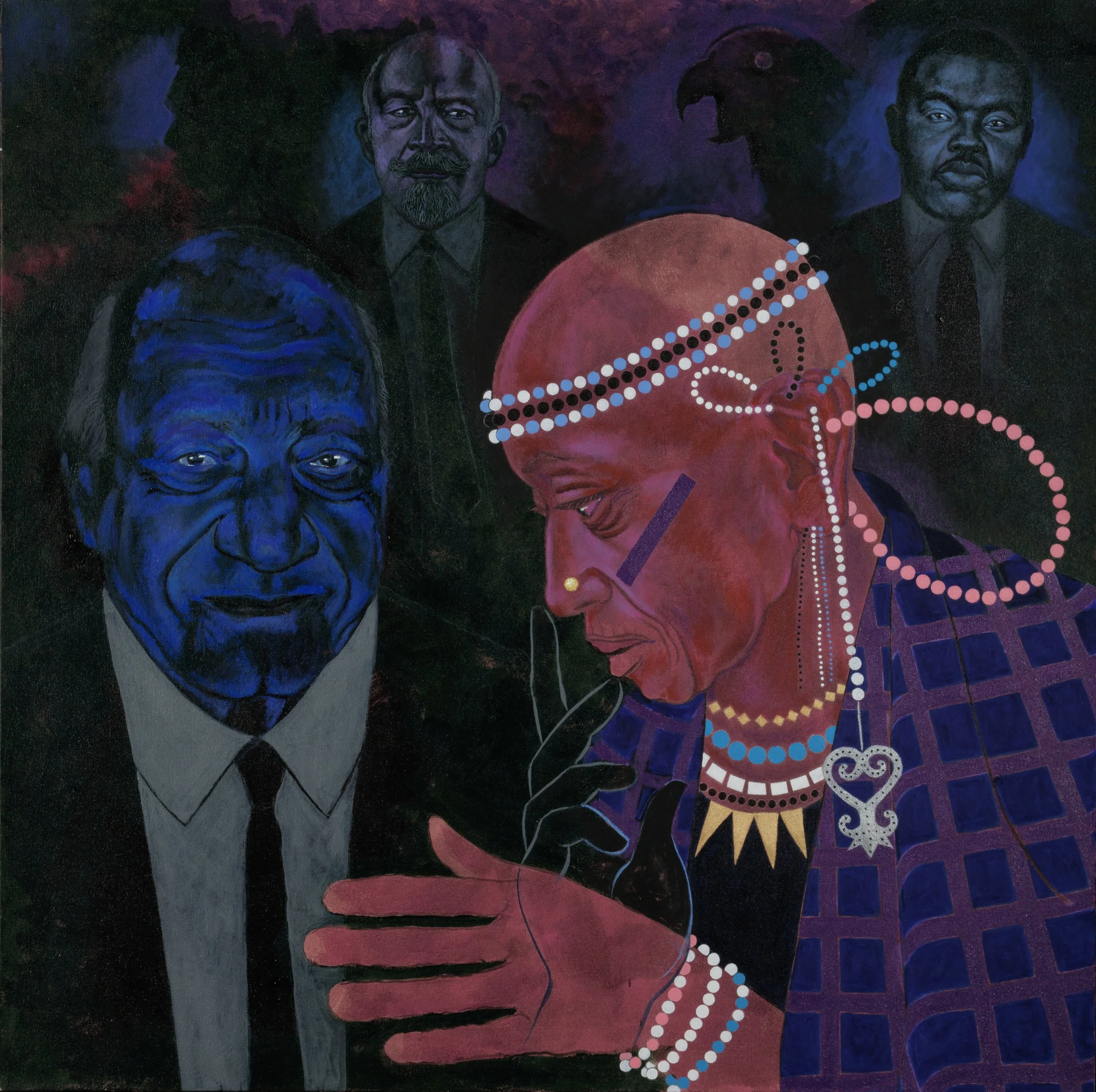

Like the preceding Burnside collection, these extraordinary 2024 works are principally grounded in dialectics of negative and positive—threat and protection, beauty and ugliness, religion and sanctity, both African and European. All this is illuminated in Blacks and the Blues by insistent intimations of the power of beauty and love coupled with the persistence and resilience of life. In raising a cry for positive change, the Burnside color and line poems, such as “Incarceration Mass for Mandela, Malcolm and Martin” reference Bahamian and African iconography and sensibilities. Counterpointing beauty is the “ugly” reflected in the age-old withholding of equality and equity from descendants of Africa. Such denials and determined lobbies to promote them, often give rise to sectorial and interpersonal violence and destruction.

Form and Style

As noted earlier, Stan Burnside leans heavily and brilliantly towards surrealism and wordplay in thematic development. He has spoken of his admiration for the work of Guyanese artist Stanley Greaves. He was particularly struck by Greaves’ statement regarding the genre: "For the European, surrealism is an intellectual exercise but, for the people of the Caribbean, it is a way of life." Stan’s own creativity has cut a highly individualist pathway in this form, attesting to the validity of Greaves’ insight. Writer and art critic Yinka Elujoba has described his affiliation and uniqueness justly: “Its hold [on Burnside] is entire, yet he wants to fashion his own language, his own light within the crowd of artists who have worked under this ideology.”

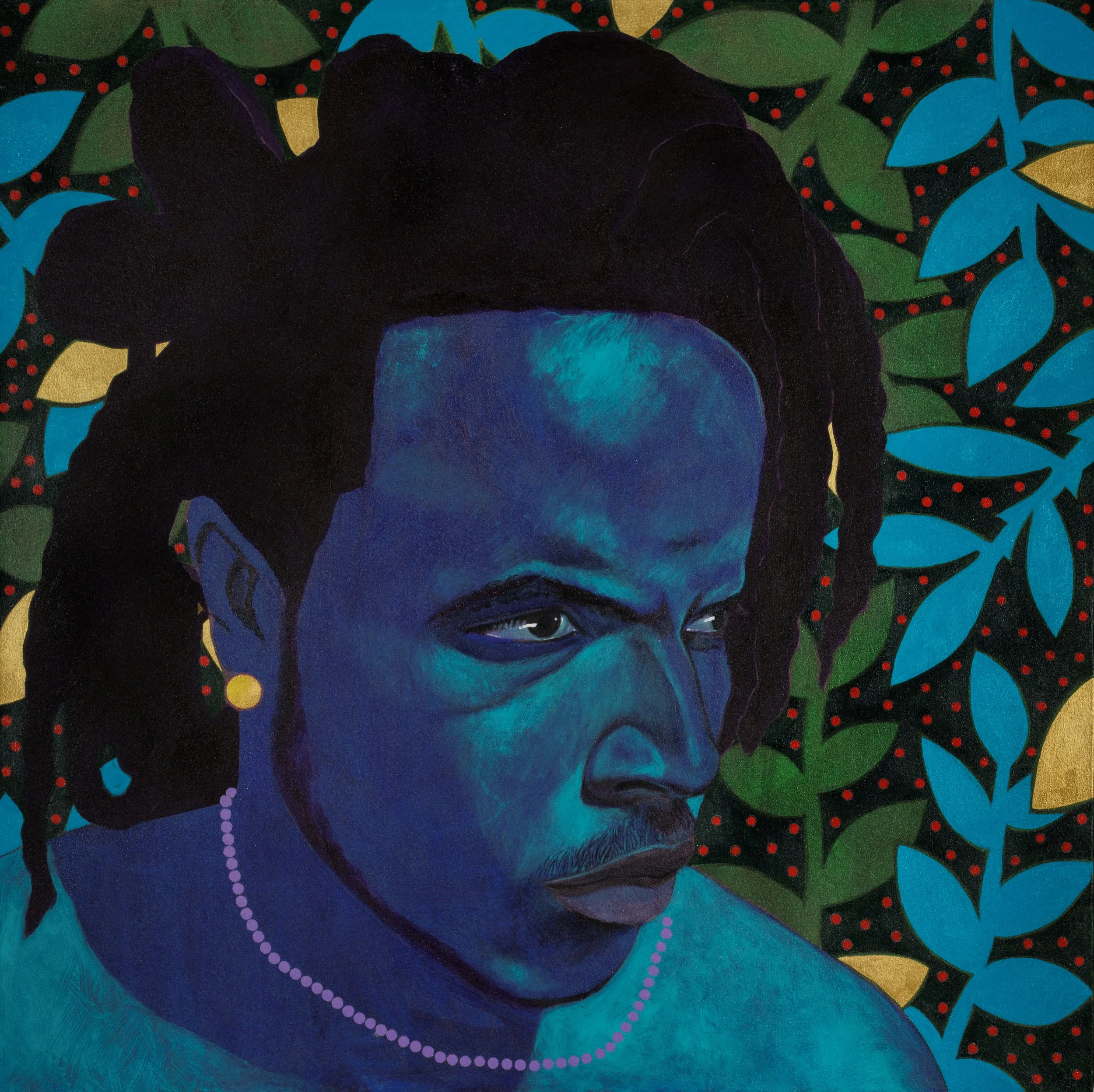

The figuration of the master is bold, highly expressive, beautiful and illuminated by a convergence of light and dark, intellectualism and spirituality. His iconography often draws a deep well of African symbolism, Bahamian folklore and Christian religion. All told, this combination yields a visual feast and clever art puzzles which invite viewers to engage in a delightful voyage of discovery to uncover the layers of encapsulated meaning.

In the paintings of Blacks and the Blues, where threat is present, there are always clear intimations of protection and hope offered in the form of gorgeous birds and West African Adinkra symbols, most commonly Sankofa. This symbol of concentric circles admonishes going back to one’s heritage and history to draw on ancestral roots and wisdom to self-emancipate and escape oppression.

Blacks and the Blues is no easily dismissible Jeremiad. Even the most hardened Philistine would find it difficult to forfeit the sensory banquet that this collection offers. Embellished by Burnside’s color alchemy, the resulting beauty requires no conscious reasoning to be appreciated, but there is much more by way of buried treasure in the paintings exhibited. The collection sets its agenda with a mindscape of signposts leading us to hidden, priceless layers of mystery and meaning. The Burnside collection thus makes highly pleasurable demands on the intellect. With greater scrutiny come greater rewards from deciphering the artistic, mental, familial, social and even playful codes of the master artist.

The strength of Stan Burnside’s drawing ability invests perceptible humanity in the portraits that regularly feature in his multi-element paintings. His achievement in this regard can be seen in the range of emotions expressed in eyes, postures, size and special positioning. We can read anger, dissatisfaction, uncertainty, reflection, love and even a spirituality attaining transcendence in some cases.

The Paintings: A Brief Review of Six

The title painting of Blacks and the Blues is eminently worthy of its name and centrality in the collection. Dominant on the huge canvas are four beautiful, superbly confident youths. They represent self-possession, self-direction, survival, selfhood and the future that captors, plantations and laws denying personhood and entitlement tried mightily to erase. Yet, life and goodness pushed through the soil of infamy and bloomed. The young woman, centrally located, holds a sheaf of black orchids. In their beauty and symbolism of strength, the flowers serve as shorthand and code for strength, determination, absolute power and authority.

Positivity and continuance are also suggested by the four animated drummers featured on a Grecian-style urn below left on the canvas. This imagery proposes that ancestral knowledge, skills and memories were not lost in the Atlantic crossing. They could not be jettisoned as spoiled cargo or leached of all value in captivity. Amidst New World discrimination and brutalities, Africa’s stolen children successfully harnessed memories and skills to sustain hope and build new communities.

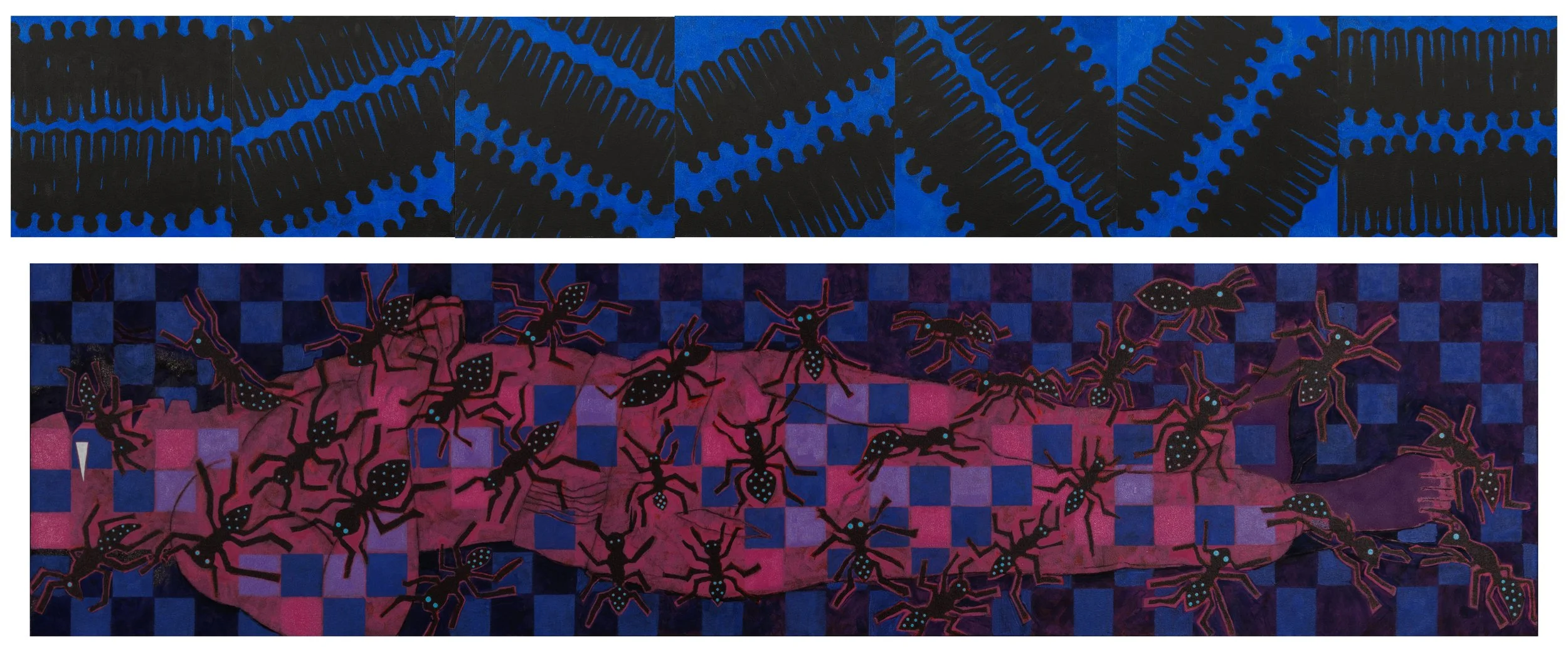

In contrast and foreboding, this lead painting tells a dark understory of slavery’s past. Given current global developments, especially in the United States, there is a subtle warning that the degradation may become current again, nullifying progress already achieved. Bearing that message is the schematic drawing of the cargo hold of a slave ship, indicating how African captives were packed to maximize control, numbers and profit. These depersonalized “goods” were shackled in precise rows, not able to move in the hot, airless bowels of the vessel, forced to void themselves where they lay for weeks in the oft turbulent and perilous Atlantic crossing. In the artist’s estimation, the all-too-ready incarceration of today’s black males echoes the dehumanization of the slave ship.

“Incarceration Mass for Mandela, Malcolm X and Martin” is a magnificent tribute to the three men named who were all jailed at some point for their involvement in black liberationist struggles—Mandela for 27 years. This striking diptych is rich in telling imagery. Here again, the title is a brilliant wordplay conveying a multiplicity of meanings. The two words, “Incarceration Mass” have undoubted religious overtones which surely refer to a funeral or memorial mass for the three heroes, as they have all passed on. They could equally represent the en masse jailing of black men today.

Another possible funereal reference is suggested by the numbers, ‘1151929 7181913 5191925,’ running across the top of the adjoined frames. These are the birthdates of Nelson Mandela, Malcolm X and Dr Martin Luther King, Jr respectively but also call to mind inscriptions on tombstones. Running like a winding stream across the two canvases are tiny images of black men dressed in prison uniforms, some tumbled upside down as if the tides of circumstance are denying them a foothold or opportunity to stand upright. This feature seems to speak both to loss of freedom and the inevitability of recurrence.

Here again, is the controlling dialectic of the collection. Here is positivity—Images everywhere affirm life, heritage and, dare I claim it—salvation. The strongly and beautifully rendered central figure releases a large bird, possibly the dove of peace, the holy spirit or hope as described in Emily Dickinson’s lyric “Hope is the thing with feathers”. For reinforcement, out of the backdrop emerge African masks and Adrinkrahene, the concentric circles signaling authority, leadership and charisma.

Consistent with the dominant thematic pattern of the collection, the canvas “Black on Black: Dust to Dust” features two women of quiet dignity. As remarked by Burnside, they are sisters and princesses. Their dignity and communion are yet another way the artist underscores the nobility that can be found among the offspring of survivors of the Middle Passage experience. Here is one of the central themes of Stan’s work—representation of a fineness of character and resilience that has defied planned extinguishment through the ages. One of the women is holding a dove-like bird, a recurrent symbol of goodness and protection. Both are seemingly ensconced in a small well of peace at the top left corner of the work. Signaling impending peril, the remainder of the canvas is filled with a confusion of angry birds in Hitchcockian-horror. Their massed dagger-like feathers portend mass violence threatening the implied stability of the family. Surely, the jeweled tempter running along the base of the painting is symbolic of the impending fall of Eden.

At the top right of the canvas, the tormented face of a young man, struggles to emerge from the tumult. He is an embattled champion in a theatre of war with a protective, shamanic shield shining clear and distinct, defying submergence. The term “Black on Black” seems to implicate the increasing, deadly conflict among young males here and elsewhere. The featured youth is perhaps fighting against his personal demons and the surrounding, attacking flock while trying to forestall the engulfing of the family by the advancing evil. The imbalance in the size of the two areas of imaging, along with the second element of the title, seems to suggest an inevitable, fatal outcome.

In the foregoing work and across canvases, exhibitions and eras, wordplay is one of Stan Burnside’s most effective and delightful signatures, formidable in their ability to subtlely convey a world of meaning. A tour de force of this Burnside code is the “Dust to Dust” of the title which echoes the funeral rites described in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. “Dust to dust, ashes to ashes” is intoned by the officiating priest while sprinkling soil on the coffin as it is lowered into the grave. Establishing this connection is deeply impactful—It is highly likely that death will result from the conflict portrayed.

With the privileging of joyful young life, “Smile” counterpoints this ominous foreboding of “Black on Black: Dust to Dust”. It is an evocation of a courtship reminding us of the gentility, communal spirit and family love that created the utopian aspect of earlier years in tight-knit Bahamian communities. The work recalls a time when young men were respectful of the prevailing customs. As was the tenor of those times, young men’s approaches took place in the protective precincts of the young women’s homes. As was also standard, and adding lightness and humor to this sensitive portrayal, parents, siblings, other relatives and even neighbours would stand watch out of sight to ensure that propriety was being maintained.

The courting couple of “Smile” appear as a pair of faces in shadow in the top left corner. The young suitor’s face is discernible, while the girl who captured his attention is almost off screen. There is a strong suggestion that they are ensconced in a darkened corner of the porch of the family home, reachable but enjoying a little privacy. Prominent in the foreground is the girl’s family keeping a discreet watch. In the foreground are two young sons; the face of the elder is wreathed in a knowing, coy smile. The parents dominate the frame. The mother, standing at right, is one of Burnside’s most beautiful women. As is expected of a caring mother, her face shows concern, perhaps that the visit in progress marks her daughter’s early steps into womanhood. The father, with locks like a lion’s mane, radiates power and benevolence. He is protective of his family and his pleasure at the situation shines in his eyes and knowing smile. His overall posture speaks to his confidence that all is well. Without a word of captioning, Stan Burnside has exquisitely rendered his view of family perfection.

“Lost in the Devil’s Triangle” exemplifies the many challenges of women, contrasted by survivalist strength. The central figure is a woman with three faces, one of which is an African mask. The face that accords with her body radiates exasperation and distress. Her unnaturally large right forearm speaks to overdevelopment from heavy labor and bearing too many weights both literal and psychological. Her neat dress and white beads can suggest that she struggles to keep face in public, while the stresses of her private life pose a threat to her sanity and survival. The points of the referenced triangle are likely home and children, outside employment and possibly church. The necklace can connote personal adornment or prayer beads as a silent appeal to heaven. There is no doubt as to the identity of the devil who negatively impacts the familial geometry and who holds the woman bound. The horned insouciant, errant husband is looking away, signaling his lack of recognition, interest or care for his partner’s overload.

“Life’s Illusions” is another remarkable painting in the Blacks and the Blues series. It is yet more reinforcement of dissonance/dissatisfaction. It features a dark blue cameo of a woman. While identifying body features are obscured, the flower in her hair and the intense gold of her earring and the ring on her finger stand out. Can we posit that her person is under or not valued, while only commodities are prized? Is the jewelry symbolic of her need to be regarded or do they speak to other desires unmet? Certainly, gold jewelry is illusory as a rung to climb to lasting happiness. They shine brilliantly at the expense of the woman who resides in deep shadow. It is clarity of vision that endows us with the ability to perceive life’s illusions and to right size the space accorded them in our lives.

The Creative Process

The depth and quality of the works exhibited at the Mestre Project at Albany, Nassau (Dec. 2024) owe much to the COVID pandemic. While Stan Burnside had never been restrained by time or circumstance from the dedicated pursuit of his creative impulses, the pandemic-related lockdowns and a studio expansion made way for increased focus on his production. It was through his wife’s great love and generosity that the entire Burnside house became a creation space. Now, beautifully evoking the wonders that will be born from canvas wombs are the odors and sights of paint, scattered tools of the trade and the artist’s paint-spattered apron. Whether public or private space, the entirety is illuminated by wonderful emergent and completed paintings.

The Continuing Emergence of an Admirable Man

Those who know him will agree that Burnside is a proudly unique soul who has forged his own essential grammar of life. He has never compromised his artistic gifts with overt political screed and pandering. Moreover, it is equally clear that he eschews allegiance to popular lobbies which, in much of 21st century art, tends to be supported by artist statements that seem to counter the artist’s truth and lived experience. Stan’s canvases are products of a man whose life reflects many layers of deeply felt, personal and societal challenges. Appearing also are explored and cherished beliefs, love, dreams and pride in family and culture. Ultimately, they are about truth as he knows it.

Reaction to Critics

“I took a lot of advice from senior Bahamian artists, particularly, and a few I have met abroad. I think it important to remember such contributions. I was especially impressed by the words of an older artist I met in Philadelphia. He told me that the only critic for a true artist is God. It's just you and God, and no matter who else approaches you, and no matter what kind of credentials they have, and all the rest of it, you make sure that you communicate with the highest power, because that's the only one that counts.

“Amos (Ferguson) never had any schooling. He never read any books but anything he ever did was museum standard. In a certain sense, I'm fortunate that people would buy some of my work, but if they didn't, I would still do it.”

Legacy:

Stan Burnside: “I’m satisfied that I’m saying what is in my heart. Everyone has a unique vision of what they are experiencing and so do I. God has blessed me with a vehicle to travel the landscape of my imagination. So, I listen to His whispers. I’m a warrior and there is much more to be done.”

Through the decades of his practice, Stan Burnside has been courageous and true to his convictions, creating an extraordinary body of work to date. Blacks and the Blues offers far more than the facile, received dicta of the 21st art world. Burnside’s paintings inform an output that resounds in receptive souls. Moreover, appreciation for his work continues to expand globally. Towards the end of 2024, Stan Burnside had a firm engagement to exhibit in Singapore at the beginning of 2025. Although retiring of habit and protective of his personal life, he extends many of the parts he holds most dearly to those true lovers of art.

Over the course of more than a month of interviews with Stan Burnside and his wife in his studio, my husband Neko and I were privy to a priceless revelation. We watched, entranced, as his paintings for Blacks and the Blues took shape. Each canvas began as a stark black expanse, a deep and seemingly impenetrable space. Slowly, subtle hints of forms would surface, embryonic life emerging from the dark void. The first signals of arrival were faint lines and delicate strokes that promised stories yet untold. With each visit, the canvases transformed further, revealing layers of shapes, color, light, and meaning. It was as if we were witnessing a journey from dusk to dawn. The once-black canvases began to scintillate with bold hues, rich textures, and vibrant scenes. Now, it was clear that Stan’s painting style marched in tandem with the dichotomies of his messaging. Unmistakable was his capturing, in the same space, both depth of sorrow and brilliance of joy, struggle birthing triumph. We had choice seats to witness the performance of a visual symphony, each movement a testament to resilience, beauty, and the powerful storytelling of Bahamian heritage and culture. Awed, we wished that more people could share in this magnificent unfolding.

It is certain that those sensitive to his artistic genius will have no difficulty in elevating Stan Burnside to the world pantheon of fine artists and addressing him as “master”.

BLACKS AND THE BLUES , 2024 Acrylic on canvas with pastel markings, 182.9 cm x 256.5 x 7.6 cm, 72" x 101" x 3"

BLACK ON BLACK: DUST TO DUST , 2022-2024, Acrylic on canvas with pastel markings, 188 x 188 cm x 7.6 cm, 74" x 74" x 3"

LIFES ILLUSIONS, 2024, Acrylic on canvas with pastel markings, 189.5 cm x 188 cm, 74.625" x 74"

ENCHANTED GARDEN, 2024, Acrylic on canvas with pastel markings, 119.4 cm x 119.4 cm, 47” x 47”

LOST IN THE DEVIL’S TRIANGLE, 2024 Acrylic on canvas with pastel markings, 119.4 cm x 119.4 cm, 47” x 47”

INCARCERATION MASS FOR MANDELA, MALCOM AND MARTIN, 2024, Acrylic on canvas with pastel markings (diptych), 119.4 cm x 238.8 cm, 47” x 94”

SMILE, 2024, Acrylic on canvas with pastel markings, 119.4 cm x 119.4 cm, 47” x 47”

HUSH...SOMEBODY´S CALLING MY NAME (TRIBUTE TO COACH CARLYLE MASON, 2024, Acrylic on canvas with pastel markings, 119.4 cm x 120 cm, 47” x 47.25”

RAMIFICATIONS, 2024, Acrylic on canvas with pastel markings, 119.4 cm x 119.4 cm, 47” x 47”

MIDDLE PASSAGE, 2024, Acrylic on canvas with pastel markings, 40.25” x 99.5”, 14” X 14” each (top canvases), 24” x 96” (bottom canvas)